Influencing Heirs And Family Incentive Trusts

Influencing the Behavior of Heirs

Published in the Journal of Financial Planning, November 2003

Copyright, 2003 FIT, Inc.All Rights Reserved.

“The parent who leaves his son enormous wealth generally deadens the talents and energies of the son. “

Andrew Carnegie.

“About half the practice of a decent lawyer is telling would-be clients they are damn fools and should stop”

Eli U. Root

To many planners and clients, the central goal of estate planning has long been to “pass as much wealth to the next generation, as tax-free as possible.” But this goal often creates a misplaced emphasis that focuses attention on assets rather than family, on structure over perspective, on tax savings over family need.

Estate planning is not fundamentally about the dead and their assets. It is about the legacy left for the living. The author believes that the first goal of estate planning is “to protect and preserve the client’s family” – a focus that starts with the living, not the dead. It is not that asset preservation is unimportant. It just pales in significance to protecting family. Tax planning and asset protection strategies should be designed around the central goal of protecting and preserving family.

There is a central truism in the passage of wealth: “Every inheritance (or lack of inheritance) will affect the recipient.” The manner and the degree to which the recipient will be affected will vary from person to person. The impact can be positive or negative, but the impact will always occur. Increasingly, clients want to influence that impact. Warren Buffett may have been speaking for many clients when he said in 1986 Fortune article: “[The perfect inheritance is] enough money so that they feel they could do anything, but not so much that they could do nothing. “ Mr. Buffet wants his wealth to create opportunities for his family while avoiding the support of unproductive lives. He is not alone in his concerns.

If the goal of protecting and preserving family is combined with the truism that every inheritance will affect the recipient, a lingering question remains: Should clients attempt to influence the manner in which an inheritance will impact their heirs? This question can only be answered in the context of the client’s personal philosophies, relationship to the heirs, and the personality, family life and character of the heirs. A detailed discussion of these philosophical issues is largely outside the scope of this article. However, these issues are discussed in a number of articles.

There are many reasons why a client may want to influence the behavior of heirs. For example:

- Protecting a child in a divorce-prone marriage by restricting control of family assets.

- Protecting a handicapped heir from judgment errors by using an independent trustee.

- Protecting underage heirs from the questionable judgment of others (e.g., an ex-spouse).

- Placing a gatekeeper on the inheritance of a known spendthrift or drug abuser.

- Encouraging grandchildren to attend college by setting up educational trusts.

- Placing no contest clauses in wills to discourage heirs from challenging the client’s dispositions.

- Delaying distributions for young heirs until they are hopefully more financially mature.

- Creating a private foundation to encourage family members to work with charities.

Should every client adopt strategies designed to influence the behavior of their heirs? Absolutely not. As planners, our role should be to thoroughly discuss with clients all of the planning options and issues. Ignoring the potential impact of an inheritance is a disservice to our clients. Unquestionably acquiescing to a client who wants to rule from the grave is also a disservice. Neither extreme is acceptable. To the degree the client wants to address these issues, this article is designed to help a planner understand some of the general approaches and perspectives.

Books on Raising Children of Wealth

* Jessie O’Neil, The Golden Ghetto (1997).

* Stephen Gadsden & Philip Gates, The New Heirs Guide to Managing Your Inheritance (McGraw Hill 1997).

* Collier, Wealth in Families (Harvard University 2001).

* Gallo, Silver Spoon Kids: How Successful Parents Raise Responsible Children (Contemporary Books 2001).

Why the Change? As shown by the list of books and articles at the end of this article, there is an increasing discussion of these issues in the marketplace. Among the reasons for this changing perspective are:

While extremely wealthy Americans, like Andrew Carnegie, often addressed the impact of inheritances on future generations, the lack of broad-based wealth in America meant that most middle-class parents (and their advisors) did not perceive that their meager bequests would have much impact – because the meager inheritance the clients received had not had much impact on their own lives. As reflected in the Millionaire Next Door, there are more affluent individuals living today than ever before. According to Boston College researchers Paul Schervish and John Havens by the year 2050 between $41 and $136 trillion will have passed to heirs and charities. See: Schervish and Havens, “Millionaires and the Millennium: New Estimates of the Forthcoming Wealth Transfer and the Prospects for the Golden Age of Philanthropy,” Social Welfare Research Institute, Boston College, Boston, MA, October 1999. Paul Schervish and John Havens have recently indicated that the expectations of the 1999 study are still valid. See: Havens & Schervish, “Why the $41 Trillion Wealth Transfer Estimate is Still Valid,” The Journal of Gift Planning, January 2003.

Until recent changes, even middle class clients faced a significant confiscation of assets from an estate tax. For example, during the 1970s the unified credit exemption amount was $60,000 to $175,000. Marital transfers in excess of $250,000 could be subject to an estate tax. The annual exclusion was limited to $3,000. In recent years transfer taxes have been sharply reduced, particularly by the tax act passed in 2001. By one report, less than 2% of deceased Americans are currently subject to an estate tax, and that percentage is steadily decreasing as the unified credit exemption increases. As a result, clients are less concerned about the impact of a confiscatory transfer tax. The focus has often shifted to the legacy they are leaving behind.

In both the media and their own lives, clients have observed the family conflicts which have erupted over even small inheritances. A pivotal goal for many clients is to reduce family conflicts.

Because of their wonderful asset protection and tax-avoidance benefits, there has been a massive growth in the number of generation-skipping and dynasty trusts. Virtually all discussions about these trusts have ignored how the massive asset accumulation in these trusts will affect future generations. It is the author’s belief that this problem is the Achilles heel of generation-skipping and dynasty trusts.

A Starting Point : When planning to influence the behavior of heirs, there are at least five primary issues which need to be addressed.

First, is the attempt to influence behavior an appropriate action? Obviously, this is largely a philosophical and personal issue, but it is one that must be addressed in the early stages of any planning. Is the client intentionally (or even unintentionally) ruling from the grave? It is the author’s view that the influences should encourage rather than punish. There are obviously fine lines between encouraging “correct” behavior and punishing “incorrect” behavior. For example, does it matter that you are indirectly punishing the grandson who does not go to college by not providing him comparable support to what is received by the granddaughter who does attend college? Does giving the grandson comparable benefits encourage him to stay out of college?

Second, the client and the planner must clearly delineate the behavior being encouraged and any behavior being discouraged and review structures which accomplish these goals. Broad statements, such as, “I want to have good grandchildren” are of little help. For example, if a client wants to encourage descendants to work, does he match the earned income of all descendants? Is there equal matching for the grandchild of minimal income who works with the homeless and the high income corporate executive of a pornography company?

Third, the approach may need to include reasonable restrictions to avoid abuse. For example, plan provides extra spending money to encourage children to go to college, the plan might require that any child must be in school on a full-time basis and maintain a B- average.

Fourth, the plan may address the possibility of new conflicts or unintended results. For example, if the plan creates that a trust to provide unlimited college funding for all descendants, what happens when a grandson is working on his fourth masters degree in advanced basket weaving? As a further example, greedy heirs may want to bust the plan to gain control over an inheritance. To discourage such attacks, the planning documents might include no-contest clauses and indemnification of Trustees provisions.

Fifth, the plan must include counter-balancing influences and flexibility to assure that the heir is not totally at the mercy of an inflexible technique or domineering decision-makers. An unchangeable approach is bound to create problems as the law, families and society change. Among the ways to add flexibility is through a limited power of appointment, which can be used to allow heirs to modify the plan for future generations. The plan should also have built-in checks and balances, such as the ability of heirs or others to remove trustees. For more information on flexibility in planning see: Barry A. Nelson & Rosario F. Carr, “Drafting to Achieve Maximum Flexibility in the Estate Plan,” Estate Planning, July 1998; Neill G Keydel & Frederick R. McBryde, “Building Flexibility in Estate Planning Documents,” Trusts & Estates, January 1996.

Values Count, But Not Too Much. Values and character generally lie at the core of a parent’s concern about how an inheritance will affect his or her children or grandchildren. Most parents do not want to encourage an unproductive descendent to live a lavish, unearned lifestyle off an inherited wealth. A U.S. Trust study of affluent Americans found that 91% of the women and 80% of the men expect their children to support themselves entirely from their own earnings. You can find this study and similar studies at the www.ustrust.com.

When discussing values as part of estate planning, it is critical to recognize that the client’s goal should be protecting and preserving family, not mandating that the client’s values be perpetuated. A parent’s attempt to enforce his or her own value systems on future generations may be counter-productive. For example, a parent who provides that anyone who marries outside of his or her race, ethnic group or religion is disinherited may be creating a conflict-laden future for his or her heirs.

Many critics argue that any attempt to influence the behavior of heirs is a not-so-subtle attempt to rule from the grave. There are clients whose desire is to rigidly control the lives of their inheritors after their death. However, if the clients’ goal is to protect and preserve family, they are not generally seeking to reach a moldy hand out of their grave. Instead, the desire may be more closely tuned to Warren Buffet’s quote: ” [The perfect inheritance is] enough money so that they could do anything, but not so much that they could do nothing.” Mr. Buffett does not want to control his children with his wealth, he just does not want it to harm them.

The difficulty lies in how to influence behavior, without exercising (intentionally or unintentionally) too much moldy control. The passage of wealth to children will not necessarily destroy them. The placement of restrictions on an inheritance is not necessarily controlling from the grave. As with any estate planning approach, it is simply a matter of making reasoned and informed choices designed to best protect the family.

Contrary to the arguments of many critics, estate planning has always included structures which influenced the behavior of heirs. For example, a Q-TIP marital trust by its nature will limit the options of a surviving spouse who cannot access the principal of the trust and will delay the ultimate distributions to children – effectively influencing the family’s behavior.

The Non-Binding Approaches. When clients are talking about influencing the behavior of heirs, the choices can be binding or non-binding. On the non-binding side, clients should consider the use of ethical wills and family mission statements. A ethical will is a free-form document which expresses the hopes, insights and concerns by an older generation to its heirs. You can obtain help in the preparation of an ethical will using Ethical Wills: Putting Your Values on Paper (M.D. Presus Publishing 2002). Other information on ethical wills can be found at www.ethicalwill.com .

Family mission statements tend to be more focused than Ethical Wills. Most are directed to particular family issues, such as how children and parents in a blended family will interact, or how family members will be allowed to participate in the family business. For example, see Craig E. Aronoff and John L. Ward, Developing Family Business Policies: Your Guide to the Future (Family Enterprise Publishers).

Clients should consider having family meetings where ethical wills, family mission statements and overall estate plan are discussed with family members. However, not every family should hold such a meeting, especially if past history demonstrates that it will only create new sources of family conflict.

The principal limitation of ethical wills and family mission statements is their non-binding nature. If there are serious concerns about the impact of an inheritance upon the inheritor, clients may want to adopt approaches that are legally enforceable.

Charitable Involvement. There has been an explosion of charitable transfers in the last several years. According to Paul Schervish at the Social Welfare Research Institute at Boston College: “A growing number of wealthy Americans are shifting their financial legacies from heirs to charity. ” According to Mr. Schervish from 1992 to 1997 the value of charitable bequests went up 110% while bequests to heirs only grew 57% and for estates above $20 million, charitable bequests went up 246% while heirs only received 75%. Many clients recognize that the charitable involvement can impact the character, values and personality of family members. In a US Trust study, 82% of affluent parents encouraged their children to be involved in charitable work.

The July 24, 2000 edition of Time magazine in “A New Way of Giving,” noted that affluent Americans are not just giving to charity, they are making sure the funds are handled in ways they approve. Clients increasingly want keep their family in control of the ultimate disposition of any significant charitable funds. As a consequence, many clients are increasingly using donor-advised funds, supporting organizations, private foundations and charitable remainder trusts in which family members can change the charitable remainderman.

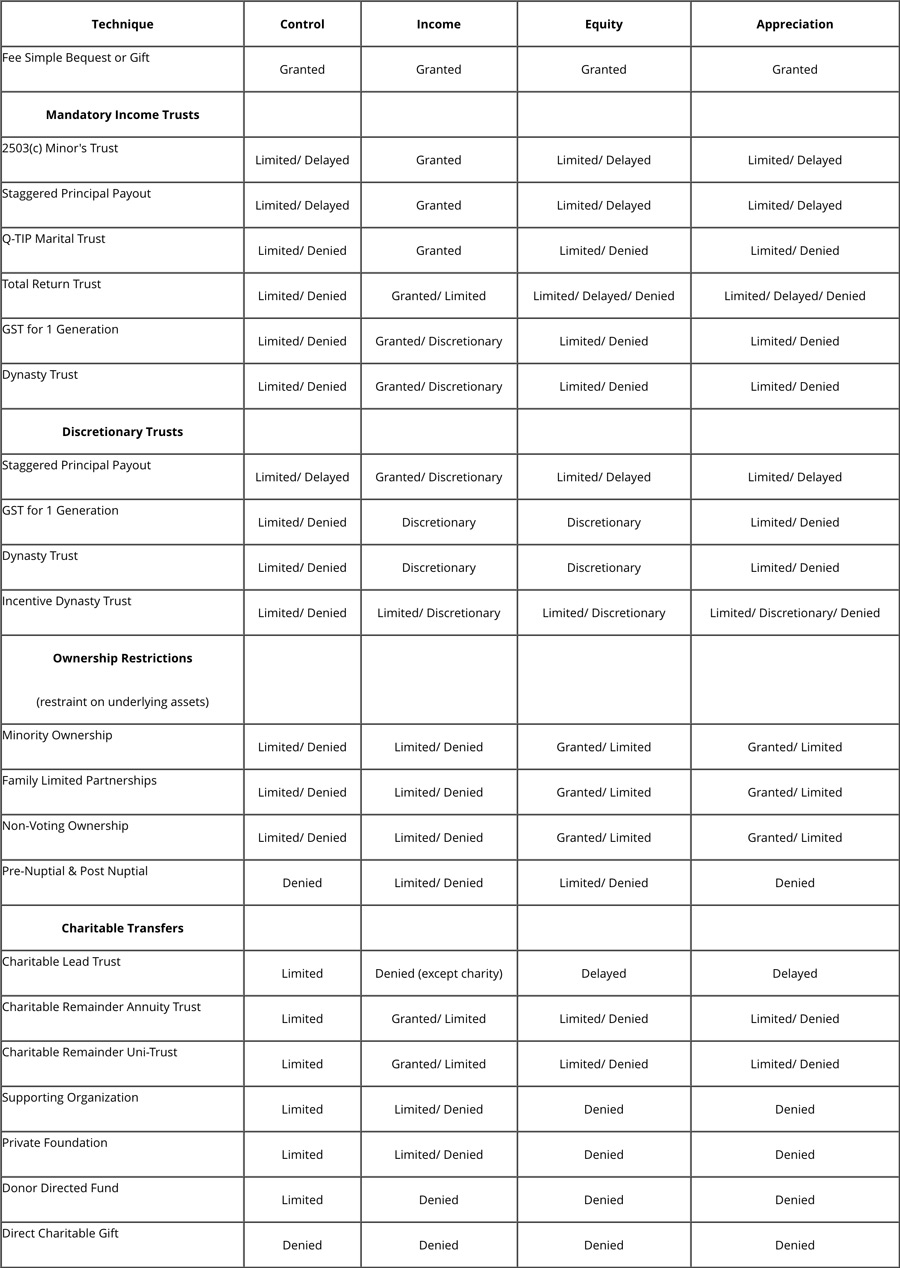

The Restraint Continuum. Any legally enforceable attempt to influence behavior by its nature includes some form of restraint on the inheritance. These restraints may be conceived of as a “Restraint Continuum”. On one extreme lies the outright, fee simple, unfettered bequest to family members. At the other extreme lies the disinheritance of family by the donation of family assets directly to a charity. Most planning occurs between the extremes.

In order to create a structure to influence behavior the planner must have an understanding of the basic elements of every estate planning technique. Virtually every asset can be broken into four parts. The division of an asset into these four elements lies at the core of every estate planning technique. These elements are:

Control. The ability to control the asset, its use and disposition (e.g., the owner of all the voting stock in an S corporation may control the corporation, while only owning 5% of the equity of the business). Income. The ability to receive the income (e.g., salary from the family business) or current benefits (e.g., use of a family vacation home) from the asset. Current Equity. The current value of the asset if it were sold. Future Appreciation . The value that the asset will grow to over time (e.g., charitable remainder annuity trust may pass all future appreciation to a charitable remainderman).

Each of these elements can be passed to heirs in at least five different ways. These approaches include:

Denied. The benefit of the element can be denied. For example, a total return trust might provide a unitrust income right to a child, but deny the child any right to other distributions.

Limited. The right to the element may be restricted in some manner. For example, a parent may have an short term interest in a residential GRIT, but be limited in the ability to use the home after the trust terminates.

Discretionary. In many cases another party will have the subjective power to decide the manner in which the heir receives the benefits of the asset. For example, in a discretionary “spray” trust, the trustee may be entitled to “spray” the income and/or corpus across a class of beneficiaries, with the decision being at the largely unfettered discretion of the trustee.

Delayed. The benefit of the element may be delayed. For example, delaying benefits based upon reaching designated ages or certain defined events (e.g., attending college).

Granted. The heir may have the current use of the element. While the heir may have the benefit of that particular element, the heir will not necessarily have the benefit of all four elements of asset rights. For example, a trust may be created which provides that all of the current income must be distributed to a named beneficiary, but deny that beneficiary the right to control benefits of current equity (e.g., corpus distributions) or the rights to future appreciation (e.g., a generation-skipping trust).

The attached chart demonstrates how these elements are normally allocated to a current beneficiary using standard estate planning techniques. Obviously, the chart is a bit simplified, but it’s purpose is not to provide an exact delineation of each technique. Instead, it demonstrates how the elements of an inheritance might be restrained – and thus influence the behavior of any heir. None of these planning techniques are new. What is new is the adaptation and reconfiguration of these techniques to satisfy non-tax , disposition purposes.

Obviously, the discussion to this point has been somewhat esoteric. Some examples may clarify the process. This article provides only some of the potential solutions to illustrate how the behavior of heirs can be impacted by restrained inheritances.

Education. A married client is concerned about the education of his grandchildren and wants to encourage them to obtain undergraduate and graduate degrees. There are a number of approaches which a client should consider, including:

The client might place annual exclusion gifts of $22,000 ($11,000 each for the client and spouse) in section 2503(c) minor’s trust for each grandchild.

Control : Delayed (until age 21) All other Elements : Discretionary (in the trustee’s hands) or Delayed (to age 21)

Unfortunately, such trusts require that the funds be distributed to each grandchild by the time they reach age 21. Access to the funds at age 21 might encourage children to leave and use the money for other purposes, like backpacking across Europe. Moreover, the trust creates no direct incentive for grandchildren to go to college. To place more control in the parent’s hands, the client might instead fund a Section 529 plan for each of his grandchildren with the parents serving as the designated “account owners” of each 529 plan. The parents would have the authority to transfer the 529 plan benefits to those grandchildren which did go to college, denying benefits to those that did not. As long as the recipient is not of a younger generation than the original beneficiary of the 529 plan, the transfer will be a non-taxable event. See proposed Treasury Regulation section 1.519-1(c).

Control : Denied (in the parent’s hands)

All other Elements : Discretionary (in the parent’s hands) or Denied (the parents could terminate the 529 Plan rights of any beneficiary)

But section 529 plans do not cover all college-related costs (e.g., they do not cover out of pocket costs and travel expenses) and do not cover pre-college costs (e.g., as private schooling). The client might consider setting up an educational trust in which trustees have the subjective discretion to decide how grandchildren receive money educational purposes (e.g., private pre-collegiate education). The evaluation might include an examination of the grandchild’s ability to fund the education costs. Included in the trustees’ discretion might be “spending money” for grandchildren who maintain a 2.5 average college grade point. The trust might provide that it would fund private K-12 schooling, one undergraduate and three graduate degrees. When the youngest grandchild reaches age 30, the trust could terminate and payout all remaining funds equally among the grandchildren. A majority of the grandchildren might be given the authority to remove the trustee, without cause.

Control : Limited (in a removable trustee’s hands)

All other Elements : Discretionary (in the trustee’s hands) and Delayed (to age 30)

There are also some ways that the client might make the plan better, including:

The plan should also consider the fact that some beneficiaries might not attend college, but would attend vocational school. Thus, the trust could also fund educational benefits for heirs who seek a vocational education.

The client might also consider matching the earned income of young beneficiaries (e.g., for summer jobs) provided they place the funds in a ROTH IRA or Coverdell Education IRA, with the intent that the funds help cover the future cost of education.

Spendthrift Child. Assume a client has a son who is a proven spendthrift. The client wants to provide income to the child, but does not want to give the son control over or access to significant funds. Among the planning alternatives are:

The client might place the spendthrift’s inheritance in a family limited partnership and place one or more family members in charge of the partnership as general partners. The general partners could be given all authority to decide how the assets will be handled and the timing and amount of any distributions to the son.

Control : Denied (in a general partner’s hands) A

ll other Elements : Discretionary (in the GP’s hands)

But such a structure may create significant conflicts within the family. It may be relatively inflexible and may be taxable when the spendthrift dies. Sibling rivalries and other unrelated issues could develop between the spendthrift and the general partners. Instead, the client could place all of the funds in a generation-skipping trust, naming a family member and an institutional trustee as co-trustees. The individual co-trustee might be given the ability to remove and replace any institutional co-trustee. The trustees might be given discretionary authority to decide whether income or principal distributions be made to the spendthrift, to his descendants or be accumulated. The spendthrift could be given a testamentary limited power of appointment to appoint the funds at his death to either his descendants or charities in such manner as he may decide.

Control : Limited (in a removable trustee’s hands)

Future Appreciation : Limited (by testamentary power of appointment)

All other Elements : Discretionary (in the trustee’s hands)

If the parent wanted a definite amount of income to accrue to the spendthrift son, the trust might be created as a total return trust, or the trust instrument might require that all of the trust income be distributed to the spendthrift.

Control : Limited (in a removable trustee’s hands)

Income : Granted

Equity : Discretionary (in the trustee’s hands)

Future Appreciation : Limited (by testamentary power of appointment)

Unstable Marriage . Assume a client has a daughter who has been divorced two times and is working on her third marriage. The client wants to make sure the daughter is provided for, but does not want the latest husband-in-waiting to inherit all of the family assets or to marry the daughter in hope of accessing those assets. The client might adopt the same approach as taken with the spendthrift child, but provide that the trustees have the ability to terminate the trust early. If the new marriage stabilized, the family member/family friend trustee could terminate the trust and distribute the funds to the child.

Control : Limited (in a removable trustee’s hands)

Income : Granted

Equity : Discretionary (in the trustee’s hands)or Delayed (if Trustee decided)

Future Appreciation : Limited (by testamentary power of appointment)or Delayed (if Trustee decided)

Good Children/Concerns About Grandchildren . Many clients have children whose personality is already developed and the clients have no concern about the adverse impact of an inheritance on these children. However, for tax and asset protection purposes, the client wants to use a generation-skipping trust. The client might consider a generation-skipping trust with the following provisions: Each child and his or her family has a separate trust. Each trust has a “spray power” allowing the trustees to distribute the income to the child or any grandchild (e.g., to fund college for grandchildren who will probably be in a lower tax bracket). Trustees may be the child and an institutional Co-Trustee. The children retain the right to remove and replace the institutional trustee with another institutional trustee. At the children’s death, the trust is held for the grandchildren in a restricted trust which allows for discretionary distributions to grandchildren only for specific events (e.g., starting a business, education, medical needs). To add flexibility, the children, prior to death, can exercise a limited power of appointment to change the manner that the grandchildren will receive benefits from the trust. If the power of appointment was not exercised, each grandchild’s trust might be terminated and distributed to grandchildren as they reach age 50.

Control : Limited (in a removable co-trustee’s hands)

Future Appreciation : Limited (by a power of appointment)

All other Elements : Discretionary (in the co-trustee’s hands)

Safety Net. The client has read the demographics and political tea leaves and is concerned that the ability of family members to receive governmental benefits is quickly diminishing. She does not want to provide a unearned lifestyle to heirs, but does want to create a safety net for her children and grandchildren. She does not want to provide benefits beyond her grandchildren. A trust could be created in which the trustee’s have absolute discretion to make distributions among the client’s descendants, or hold the funds in the trust. The trust might provide broad directions on how the grantor would want distributions to be made (e.g., to provide for basic medical, education, living and long term care benefits for those who are unable to afford them). A super-majority (e.g., 80%) of the descendants might have the right to remove any trustee with approval of a least one of the remaining Co-Trustees. After the death of the last of the client’s grandchildren all the trust funds could distributed to a designated charity.

Control : Limited (in a removable trustee’s hands)

Future Appreciation : Denied or Limited (passes to a charity)

All other Elements : Discretionary (in the trustee’s hands)

The Family Business. For many entrepreneurs, the family business is the largest single asset of their estate. As a result the owner often passes part of the business to other family members who are not involved in the business. During the entrepreneur’s lifetime they may have been able to maintain peace in the family and serve as the “benevolent dictator” of the family business. Unfortunately, this powerful role disappears with the entrepreneur’s death or incapacity. Sibling rivalry and other issues begin to come to the fore, particularly between those who are operate the business and those who are outside the business. This conflict is often inevitable as each family member attempts to direct his or her own financial destiny and feels increasingly unable to do so because of the common business ownership with other family members. This is not a matter of “good” and “bad” family members. It is a matter of increasingly different life goals – a normal part of life.

The outsiders may feel that the compensation and perks provided to the insiders are “excessive.” Outsiders will question the business decisions (e.g., capital expenditures, hiring and firing of family or friends, expansion plans) of the insiders even when they know little about the business’s needs, operations or competition. Outsiders often believe that the income paid to them should match the compensation paid to the insiders. Meanwhile, the insiders (who may feel they are working much too hard) resent that their sweat is increasing the equity value of the outside family members who are continually asking for more income to which they are “not justly entitled”. The insiders may fail to see that the outsiders have a right to a return on their “investment” in the business. Many family businesses have paid huge legal fees because of these conflicts and/or have been forced to sell the business to alleviate the problem.

The solution lies in setting up a structure in the estate plan which assures that those in the business own and control as much of the business as possible, while giving outsiders other assets so that they can effectively control their own financial destiny. Life insurance is often a necessary element of this planning. This planning process traditionally must be done by the entrepreneur during life so the entrepreneur can dictate the terms to family members. Often this process will recognize the contribution to the business of those who have long term involvement by passing a disproportionate part of the business to the insiders.

This is actually two tiers of influence. First, the client has adopted a structure to reduce family conflicts over the business. Second, once the decision has been made to pass business interests only to those in the business, the planner must address the manner in which each group will receive benefits. For example, if insurance is used to equalize benefits, do the children own it directly, or is it placed in a generation-skipping life insurance trust? If a family business is being passed to those who run it, does the family adopt a Family Mission Statement on how family members will be entitled to be employed in the business?

Conclusion

Creating a plan to influence the behavior of heirs cannot be done cavalierly. It requires a detailed knowledge of the available planning techniques and a thorough understanding of human psychology and the client and the client’s family. It will from time to time require the planner to follow Mr. Root’s advice which was cited at the beginning of this article. It will also require more time than a standard-form, tax-avoidance driven strategy.

Will the adoption of these techniques assure a “perfect legacy”? Perfection is beyond the grasp of any of us. No approach can produce perfect descendants. These concepts do hold the potential for minimizing the negative legacy of an unfettered inheritance – by recognizing the inherent risks of passing unrestrained wealth. Addressing these issues can limit the exaggerations which often occur when significant wealth is passed, without thoughtful consideration, to the future generations.

*************

Author : John J. Scroggin, J.D., LL.M. is a graduate of the University of Florida and is a nationally recognized speaker and author. Mr. Scroggin has written over 300 published articles, outlines and books, To be added to his free blast email system on estate and income tax planning, contact [email protected] . “The Restraint Continuum” is a registered servicemark of FIT, Inc.

Materials on Wealth and the Impact of an Inheritance

Books:

* Andrew Hacker, Money: Who has How Much and Why ,

* Thomas J. Stanley, The Millionaire Next Door and The Millionaire Mind

* Scott C. Fithian, Values Based Estate Planning .

* John J. Scroggin & Robert Littell, The Family Incentive Trust, National Underwriter.

* William H. Gates, Sr. and Chuck Collins, Wealth and Our Commonwealth ,

Articles:

* “Should You Leave it To Your Children.” Fortune , September29, 1986.

* “The Perils of Family Money,” Forbes , June 19, 1995.

* “The Market Value of Family Values,” Cato Journal (Winter 1997); www.acfc.org/essay/cato1

* “The Disinheritors,” Forbes , May 19, 1997.

* “Two Cheers for Materialism,” Wilson Quarterly , April 1, 1999.

* “Inheritance and Sloth,” Forbes , October 11, 1999.

* “Family Feuds, Financial Planning , November 1999. •C “Family Incentive Trusts,” Journal of Financial Services Professionals , July 2000.

* “Passing it On: Will Older Americans Show Their Children the Money?” Journal of Financial Planning , August 2000.

* “The Psychological Impact of Sudden Wealth,” Journal of Financial Planning , January 2001.

* “Unwise Wisdom: Leave All Your Money to Your Children,” Wall Street Journal , page R11, January 29, 2001..

* “Giving Something Back: A Golden Age of Philanthropy May be Dawning,” The Economist , June 6, 2001;

* “Rich Man’s Burden: Too Much Money Can be Bad for You in All Sorts of Ways,” The Economist , June 16, 2001.

“Tough Will Saves Troubled Daughter,” Trusts and Estates , July 2002.

“Leaving a Legacy: A Client’s Search for Meaning,” Journal of Practical Estate Planning , September 2002.

“Restraining an Inheritance can Accomplish a Client’s Objectives,” Estate Planning , March 2003.

“Six Dimensions of Wealth: Leaving the Fullest Value of your Wealth to Your Heirs,” Journal of Financial Planning , April 2003.

The Restraint Continuum

(normal benefits to a current individual beneficiary or owner)

Note: To be workable, the table over-simplifies the restraint options available with each planning technique.

FAMILY INCENTIVE TRUSTS TM

Copyright, 2000. John J. Scroggin, J.D., LL.M., All Rights Reserved.

Earlier Version Published in the Journal of Financial Service Professionals. July 2000

“The primary goal of estate planing is to protect and preserve the family,

not to protect and preserve family assets.”

A revolution is beginning in the estate planning industry. Until recently, the traditional goal of estate planning has been to pass as much wealth on to the next generation as tax-free as possible. The avoidance of taxes and the passage of maximum wealth are increasingly being displaced by other goals. Personal issues are becoming the driving force in the estate planning process. This change is a result of numerous demographic, industry, and societal changes, including the following.

First, there has been an explosion of wealth in this country in the last two decades. It is estimated that somewhere between $10 [i] -136 [ii] trillion will pass in the next 40-50 years. It is not just the wealth, but also the demographics of that wealth (and related perspectives and implications) which are driving the revolution. For example, according to a recent study by US Trust [iii] the following statistics were noted.

Only 10 percent of today’s millionaires inherited their wealth. [iv] As pointed out in Forbes magazine: A To New Money nothing outclasses achievement. Wealth that one possesses but did nothing to earn – or at least add to – is viewed as frivolous. [v]

Forty-Six percent of today’s millionaires became millionaires from their own businesses. Anyone who has created a business from scratch understands the monetary, mental, and physical stress that comes from growing a successful business. However, it also gives a profound sense of accomplishment, which many business owners would like their own descendants to experience, but without all of the hardships.

The average millionaire comes from a middle class or lower background and has worked his or her way through college. Many of these people recognize that their early struggles provided them the sense of self-worth that made them successful later in life and, hopefully, fulfilled.

The average millionaire works a 56-hour work week and has worked for over 29 years. As the above quote in Forbes implies, 90 percent of today’s millionaires who are New Money see hard work, not as an alternative, but as an obligation.

Twenty-seven percent of the average millionaire’s after-tax income is invested. One central point of the Millionaire Next Door [vi] was that these Americans were not extravagant; they saved rather than spent, and they want their children to do the same. Too many have seen heirs dissipate an inheritance on a lavish lifestyle.

Eighty-three percent of today’s millionaires expect their child to contribute to the cost of his or her own education. Something given is never as valuable as something earned.

Ninety-one percent of the women and 80 percent of the men expect their children to support themselves entirely from their own earnings. They will provide opportunities, but lifestyle support is not in the cards.

The two highest goals parents have for their children are finding a satisfying career and supporting themselves and their families. Financial success is a low priority. Inherent in this perspective is that doing what you like, not wealth, brings fulfillment. Having seen wealth up close, the average millionaire understands its illusions.

Only 64 percent of the millionaires say their children will inherit their wealth. While this seems to be a large percentage, it means that 36 percent have decided that their children, for whatever reasons, should not inherit their wealth.

On average, millionaires feel $5.5 million is the most they can pass to an heir without it impacting the heir’s character.

Other studies provide similar insights.

According to The Millionaire Next Door [vii] , 66 percent of today’s millionaires are self-employed. Work is a fundamental issue for the millionaire next door.

A 1992 study showed that almost 20 percent of the people who inherited as little as $150,000 quit working. [viii]

In a recent study, [ix] 44 percent of the persons polled indicated they would quit work if they received a sizable inheritance. Interestingly, the higher someone’s salary, the less likely they would quit working. Fifty-four percent of those with salaries below $125,000 would quit, while only 28 percent of those with salaries above $250,000 would quit.

A 1993 study [x] indicates that over 20 percent of Americans do not have children to whom to bequeath assets. In many cases, this group is less willing than parents to provide remote heirs a unearned lifestyle.

In a recent Gallup poll 2/3 of the peopled polled believe that their children will have a more successful financial future than the parents did. [xi] This underlying confidence may comfort parents with the thought that they children will not have to survive on their parent’s inheritance.

The Wall Street Journal on March 15, 1999 [xii] reported that US households held $10.77 trillion in marketable securities at the end of 1998.

According to a study in Investment News [xiii] , the number of households with over $1.0. million in investable assets is expected to increase from 2.5 million in 1998 to 3.5 million by 2003.

USA Weekend [xiv] reported that the average baby boomer will inherit approximately $90,000.

According to the Federal Reserve Board the following wealth exists in America:

Estate Value % of Households Total % of All Net Worth

Over $2.7M 1% 35.1%

$394,000-$2.7M 9% 33.2%

$250-394,000 3.7% 5.5%

$100-249,000 21.8% 16.4%

Under $100,000 64% 9.8%

According to the New York Times, [xv] on average, the greater the estate, the less the percentage which is expected to pass to heirs:

Estate Size To Taxes To Heirs To Charity To Costs

Over $20M 34% 23% 39% 3%

$1-5M 22% 66% 8% 4%

The same study shows that for estates below $1.0 million, 90 percent will pass to heirs. The study supports the impression in the estate planning field that the wealthier the client, the more assets which pass to charity instead of heirs.

Second, states are opening up new trust planning alternatives with the elimination of the rule against perpetuities and the liberalization of spendthrift trust rules. The rule against perpetuities is part of the English common law. Trusts were not permitted to exist in perpetuity. Instead, the King required that trusts terminate within a life in being plus 21 years. At least six states have eliminated the Rule Against Perpetuities. These states are Alaska, Delaware, Idaho, Illinois, South Dakota and Wisconsin. Like the tidal wave of limited liability company legislation, other states are moving to enact statutes which eliminate the rule

A spendthrift trust is a trust in which the claims of creditors of beneficiaries are restricted. Traditionally, a grantor could not create a spendthrift trust for his own benefit, but a number of states have begun to allow such trusts, with certain limitations. No longer does a client have to create an offshore trust to protect assets from creditors. The client can move the assets to an Alaska, South Dakota, or Delaware trust [xvi] which can exist in perpetuity.

These state law changes create an expanding interest in the use of dynasty and spendthrift trusts as a part of the estate planning process. While dynasty trusts provide significant inter-generational estate tax savings, many clients are more interested in their spendthrift provisions and the ability to use such trusts to protect future generations from creditors and divorcing spouses.

Third, increasingly clients are focusing their attention on non-tax issues. Many have come to realize that their families have more to fear from the negative impact of wealth than they do from the confiscation of their wealth by the federal estate tax. As Katherine Gibson of the Inheritance Project has said: A The guilt and shame of inheriting wealth increases with each generation. The farther a generation is from the initial creation of wealth, the greater the guilt and shame become [XVII.] Instead of estate taxes driving the planning process, increasingly clients’ personal desires and goals are driving that process. Any inheritance will have an impact on future generations. More and more, clients want to manage that impact, so it is positive rather than negative.

As shown in the Appendix, the last several years have seen a surge of magazine and newspaper articles discussing the negative aspects of inherited wealth. Many of America’s wealthier citizens have decided to pass most of their assets to charities [xviii] and [xix] private foundations rather than to their families. A 1986 Fortune article captured this concern: There is nothing people like me worry more about – how the hell do we keep our money from destroying our kids?

The issue of the satisfaction of wealth is not a new one. Families have struggled with it for centuries. In Ecclesiastes 5:10-11(NIV), Solomon wrote: Whoever loves money never has money enough; whoever loves wealth is never satisfied with his income. This too is meaningless. As goods increase, so do those who consume them. And what benefit are they to the owner, except to feast his eyes on them? What is new is the massive wealth which reaches across a broader spectrum of Americans and the desire of many of these self-made millionaires to create a better legacy for their children.

Fourth, the author believes that the first three revolutions are beginning to create a radical change in the nature of trustee responsibility. Many trustees have perceived their primary fiduciary responsibility as protecting and preserving the assets of the trust. Increasingly, clients instead are telling the trustees that their first responsibility is to preserve and protect the family rather than the assets.

This radical shift in perspective is changing the nature of a trustee’s responsibility by mandating that there be more discretionary judgment authority in the hands of the fiduciary than has traditionally been the case. The discretionary judgment decisions are more critical and elusive than standard trustee responsibility and are creating significant changes in how trustees are approaching their responsibilities. In some cases, this trustee responsibility may rise to the level of serving as a financial mentor for beneficiaries, training them in financial stewardship and responsibility.

The fifth change has been the increasing movement of non-lawyers into the estate planning field. With trillions of dollars getting ready to pass in the next 20 to 30 years, many other professionals are recognizing the value of moving into this lucrative field. Financial planners and CPAs increasingly are going after this type of business or expanding the range of estate planning services they provide. For example, CPAs are selling insurance products and taking over the administrative functions of trust and estate management. Financial planners are providing sophisticated estate planning advice, and brokerage houses are creating trust companies In addition, the professional barriers which once walled off each profession from the other are beginning to fall. Many people believe that it is only a matter of time before all estate planning professionals effectively operate under one banner. The continuing debate in the American Bar Association is but one example of this struggle.

What is the net result of these changes? One result may be that increasingly professional practices will be driven not by the profession of the advisor, but rather by the nature of his or her practice. For example, estate planning may increasingly become a business interest in itself, with a single firm offering tax advice, fiduciary services, tax compliance, probate and trust administration, drafting, financial products, and even psychological advice.

One other result is a creative revolution in how clients are addressing their estate plans. As the materials listed in the Appendix attest, increasingly America’s self-made millionaires are focusing their attention on how their wealth will impact future generations. Although many millionaires have determined that substantially disinheriting family is the best solution, it may be that the question has not been properly addressed. The perspective for most clients is not: A To give money to charity to avoid spoiling their family, but rather to provide opportunities for family, rather than giving them a lifestyle that means they never have to work. Clients want their families to contribute to society and to be responsible.

Increasingly estate planners are raising with their clients the idea of placing constraints on transferred wealth rather than disinheriting future generations or giving them an unearned, affluent lifestyle. The intent and hope of such restraints is to create opportunities and incentives for future generations without supporting an unearned lifestyle. As Warren Buffet has been quoted: [The perfect inheritance is] enough money so that they feel they could do anything, but not so much that they could do nothing. [xx]

The wealthy client often has three goals for his family. First, the client wants to protect his or her family from ever being destitute . Many of these clients have been destitute and recognize how hard it is to drag oneself out of that hole. Second, they want to provide opportunities to their family. They hope their descendants will take those opportunities and mature because of their own sweat and blood. Finally, they do not want to provide a non-working lifestyle to their heirs. Giving a child a healthy annual income more often than not takes away any ambition and these self-made millionaires know this better than most. As Andrew Carnegie said (as he gave his wealth to public libraries and charity): The parent who leaves his son enormous wealth generally deadens the talents and energies of the son and tempts him to lead a less useful and less worthy life than he otherwise would. [xxi]

The Growth of the Dynasty Trust

One solution to these client concerns is a new estate planning concept called the Family Incentive Trust. [xxii] But, before discussing the Family Incentive Trust, a greater understanding of dynasty trusts is essential. While there has always been substantial focus on saving estate taxes, until recently there has been less focus by planners and clients on the inter-generational confiscation of wealth. That is, as each generation dies, up to 55 percent of their estate is taken by the federal and state transfer taxes. As illustrated in Diagram 1, at each generation break, the government takes 55 percent of an estate.

A dynasty trust is a generation skipping trust [xxiii] designed to exist for the maximum period permitted by applicable state law – the so called Rule Against Perpetuities. [xxiv] As shown by diagram 2 it can provide benefits to successive generations. In those states which have eliminated the rule against perpetuities, generation-skipping trusts can be created to exist forever. If the approach is adopted, the trust instrument may make some provision for termination – such as allowing the trustees by unanimous decision (perhaps with approval of a majority of the adult beneficiaries) to terminate the trust.

Especially for family business interests and insurance trusts, the dynasty trust may be an excellent tool to avoid future estate taxes for family members.

If the dynasty trust is created as a spend thrift trust, state law may restrict the right of creditors and divorcing spouses of family members to access the funds held in the trust. Moreover, because the assets are held in trust and not by the family members, the management of the trust assets may be retained in the most competent hands. For example, professional money managers, or family members who run the family business versus family members who may be prone to making bad investment decisions.

Planners are increasingly examining the benefits of a dynasty trust. Numerous practitioner articles have appeared recently discussing the concept. [xxv] Increasingly, banks are focusing their attention on dynasty trusts as a new product to the consumer market. [xxvi] Consumer publications are also informing readers of the merits of dynasty trusts. [xxvii]

Why does a dynasty trust make sense? Take a close look at the inter-generational confiscation of wealth as shown in Table 1. Assume an trust starts with $1,010,000 in 1999 and grows at a six percent rate per year. Every 25 years, a generation dies, and 55 percent of the accumulated wealth is confiscated in federal and state estate taxes. The lower line in Table 1 shows the tax impact (assuming the family did not spend the funds to support a lifestyle) over 77 years.

Instead of losing 55 percent of the estate to a confiscation tax every 25 years, the dynasty trust continues to grow, and the compounding of the funds which would have been paid in estate taxes results in significant growth in the value of the trust’s assets. Virtually every client wants to avoid estate taxes. As shown in Table 1, in 77 years almost $80 million is held in the dynasty trust versus $7.3 million held by the family. Not only did the government take 55 percent of the family assets three separate times, but the government also receives the benefit of the growth on those assets. Shown the above calculations, many clients have seen the benefit of avoiding the inter-generational confiscation of wealth.

Because the trust may exist forever, it cannot be cavalierly created. It requires considerable thought and expert drafting. Poor drafting is bound to increase family conflict and litigation. Because these trusts are irrevocable, many people believe they must be inflexible. This is not the case. Most state laws contain relatively few restraints on what can be provided for in a trust instrument, except those which violate public policy. For example, the following provisions would violate most states’ public policy and be unenforceable: Give $100,000 to my daughter if she divorces that bum she married, or disinherit my son if he marries outside my race.

Through creative and flexible drafting, a living document can be created – a Perpetual Estate Plan tm. for future generations. These flexible approaches are discussed in more detail later in the article.

However, the dynasty trust creates an inevitable issue: What will be the impact of that accumulated wealth on future generations? Referencing back to Table 1, assume a great-grandson has a right to 10 percent of the dynasty trust in 77 years. His 10 percent interest entitles him to benefits from almost $8 million of the trust principal. With a six percent return per year, his annual income for the rest of his life is almost $480,000. When his father tries to convince him to go to college, the son’s response is: With a half-million a year, why go to college? Why work? This illustration points out the damaging effects of inherited wealth and the reason that so many clients are unwilling to pass all of their assets to family members. This concern is also reflected in the materials in the Appendix.

Family Incentive Trust TM .

One solution to this problem is The Family Incentive TrustTM ( FIT). It is designed to create opportunities and minimum protections to family, without supporting future generations with an unearned lifestyle. The FIT is typically a dynasty, irrevocable, generation-skipping trust, which provides benefits across future generations. As discussed below, unless truly destitute, no family member can live off the trust funds!

At its most basic level, the FIT is simply a method of disposing of assets. It addresses the core issue with which many clients are concerned: How to pass an inheritance in a manner which cause the least amount of damage to the character of future generations. In addressing this issue, the FIT creates a system in which family dispositions are made for three primary purposes:

To provide a safety net for future generations;

To create positive incentives to encourage responsible behavior in future generation; and

To provide a fund for family loans and investments in family businesses.

Not all clients will adopt every FIT feature discussed in this article. That’s what makes the tool so versatile. The FIT is not a rigid plan that the client has to fit his or her goals into, rather the client’s goals drive the structure of the Family Incentive Trust. To some this flexibility is inordinately complex, but that is the inherent beauty of the Family Incentive Trust – it is not a boilerplate, one-fits-all document. Rather, it is a document which is driven by the client’s personal goals and concerns, not taxes. It requires both the planner and the client to think outside the box.

The clearest way to think about the FIT is: It is the body which can FIT on the chassis of virtually any other trust. The FIT focuses the estate planning process on the manner in which inheritance distributions are made to a client’s family and then designs the estate planning documents to fit around the client’s desires.

Because it is driven by the client’s desires and factual situation, no two Family Incentive Trusts are the same. Although the author believes it is in the best interest of the client’s family to have FIT features in any dynasty trust, not every FIT is a dynasty trust. For example, some clients place restraints on their family’s inheritance for a period of time and then pass the assets to the heirs at certain designated ages. A unified credit trust may provide that income or principal may be sprayed to children using FIT provisions during the surviving spouse’s life, with the funds being distributed to family members (at designated ages) after the surviving spouse dies.

The FIT places constraints on inheritance and assures that no family member can live a lavish lifestyle off the family inheritance. While it may not eliminate all the negative consequences of inherited wealth, it can substantially reduce them.

The Family Incentive Trust is merely an alternative approach to the disposition of assets. The FIT is designed to become a part of virtually any type of trust created for estate planning purposes. Thus, the FIT can be part of:

An insurance trust,

A charitable lead trust (but not a charitable remainder trust),

A living trust,

A unified credit trust created by will,

A unified credit trust created during life,

A reverse Q-TIP, A trust created after the termination of a marital trust,

A Crummey minor’s trust,

Any generation skipping trust,

An asset protection trust, or a

A defective grantor trust.

Because the dynasty trust is often a part of the FIT, the trust must be designed to account for its long-term existence. Providing flexibility is critical. Much like the US Constitution, the FIT is designed to be a living document which can deal with the family issues that may arise across the generations. It is designed to deal with such issues in a practical manner, not in a legally restricted manner.

The Family Incentive Trust begins with the practical question: How does the client pass his or her wealth to heirs with the least amount of damage? It then builds the entire estate plan around the answers to that question. Instead of tax avoidance directing the estate plan, the client’s hopes and desires for future generations direct the plan. This type of plan often requires intense discussions with the client, because many clients have never examined the issues which the FIT addresses.

The FIT is flexible enough to meet the client’s particular facts. Consider the following examples:

A client with children who are older and have good character can provide that the trust gives their children income for life, and then becomes a FIT for grandchildren. A special power of appointment can be used to allow each child to change the disposition for their own children.

A client with no children may create a FIT for nieces and nephews.

A client with young children may create a FIT that accumulates income until the children become adults and then becomes an operational FIT.

The FIT does not generally contain a requirement that the trustees provide health, maintenance or support to any beneficiary. Normally, even the safety net and incentive distributions are left to the discretion of the Trustees. The purpose of this is twofold.

If a support standard is provided in the instrument, it increases the chance that a descendant will sue to require support at the level the beneficiary deems appropriate. By leaving the distributions to the total discretion of the trustees, this possibility is reduced.

The FIT is designed to supplement any governmental support the beneficiary may be entitled to by law. In a series of cases, state governments have been successful in requiring a trust to be the first source of support where a support obligation existed in the trust instrument. With the FIT having a number of beneficiaries and the trustees having absolute discretion in who receives any distribution, the possibility of the government forcing invasion of the trust is reduced.

The language of the trust instrument sets the criteria that the client wants the trustees to use in making trust distributions. While the trustees must use those criteria in exercising their discretionary authority, they can decide not to make distributions because of other known facts. The trustees are generally not given the authority to add new criteria. This reliance upon trustee discretion is one of the pivotal ways that the FIT is designed to be a living document.

The FIT is normally a spendthrift trust. A spendthrift trust is any trust which provides for three major restrictions.

It restricts the ability of any beneficiary to assign or otherwise transfer his or her interest in the trust. In most states, a trust right is freely assignable by the beneficiary. For example, as collateral for loans or for other personal purposes.

A spendthrift trust restricts the rights of creditors of a beneficiary to demand payment of income or principal to satisfy the debt obligations of the beneficiary. In some states creditors are still free to garnish actual distributions to the beneficiary but are unable to force distributions in order to garnish them. In some states certain creditors, such as the government, may pierce a spendthrift trust. Other states severely restrict limitations on the creditors of a trust beneficiary.

Because the trust owns the assets (and not the beneficiary), a divorcing spouse is generally unable to force distributions from the trust as a part of any divorce decree.

A Family Incentive Trust is not a solution to every estate planning issue. For example, if the FIT is created as a generation-skipping dynasty trust, a donor’s contribution to a generation-skipping trust is restricted to $1,030,000 (in 2000). Provisions must be made for the disposition of the client ‘ s other assets. The FIT is just one part of the overall estate plan. For example, for many clients the use of the FIT allows them to feel more comfortable about passing other assets to charities.

FIT Distributions

Any trust has two sources from which to make distributions: income (for example, interest, dividends, rent) and principal (for example, as the assets owned by the trust, such as real property, cash, and stocks). The beneficiaries generally will be taxed on the trust income distributed to them. Principal distributions are often tax-free.

Safety Net

The safety net is designed to protect the family from life’s disasters. In the FIT, the safety net is first funded from available income, and if the income is insufficient, principal can also be distributed. If necessary, all income and principal (in the trustees’ discretion) can be expended for this purpose. This provision assures that the protective purpose of the FIT is not limited by the income of the trust. Any safety net distribution is needs based, as determined by the trustees. The safety net is defined by the creator of the FIT, but it normally includes:

Providing supplemental aid (after any governmental benefits) to any destitute beneficiary,

Providing medical aid to needy beneficiaries,

Providing educational help to needy beneficiaries, and

Providing long-term care help to needy beneficiaries

The safety net has the highest priority for the trustees. Only after distributions are made to provide these minimum protections are other distributions made. The trustees can take into account future distribution needs in deciding how the remaining trust funds are used.

Incentives

While the incentive nature of the FIT has received the most press, it is only one part of the Family Incentive Trust. Based upon the client’s desires, the incentives can be made solely from remaining trust income or from both income and principal. Most clients choose to fund incentives from both income and principal. Some incentives are restricted to only income, and if there is not sufficient income, distributions may not be made. For example, clients, who provide an incentive which matches their descendants earned income, often restrict the incentive to distributions from the trust’s available income.

The incentives are designed to provide incentives for positive behavior by the beneficiaries. The incentives are at the core of the Family Incentive Trust and generally involve the most time spent with the client. The incentives may be broad (for example, provide spending money to descendants who are in college), detailed (for example, provide for the cost of driver education for future generations), or charitable (for example, provide for descendants to be overseas missionaries). To date over 35 different incentives that clients have used have been identified.

It is strongly advised that clients address the incentives from these perspectives.

* Stress the positive, not the negative in creating the incentives. Negative incentives tend to be counter-productive.

* Because the trust will be in existence for a long time, minimize the restrictions on any incentive – instead rely upon the judgement of the trustees by giving them broad authority.

* Because the incentives are designed to promote positive behavior for beneficiaries in their formative years, people often restrict the incentives to their descendants or the descendants of the named family (i.e., providing them to spouses of descendants does not normally make sense).

Build flexibility in the trust so changes in values can be accommodated in the future. For example, using special powers of appointment, each generation can reconfigure the trust terms for the next generations.

Clients sometimes express concern that the above distributions may dissipate the trust. However, such concerns are based upon a different goal: Maintaining as much wealth as possible. The FIT goal is not to maintain the wealth, but rather to use it for future generations in the most productive ways possible. It is designed to use wealth productively. The intent is not to distribute the money quickly and, therefore, dissipate the wealth, but rather to distribute the funds responsibly.

The goal of the trust is not to preserve the principal and income of the trust. It is to provide a safety net, encourage responsible behavior, and provide future opportunities to the family. Thus, trustees are given broad authority in deciding which distributions should be made

After provisions are made for the safety net and incentives, any remaining income is either distributed to charities or accumulated in the Trust. No family member can live off the trust!

Family Investment Bank

The principal can also be loaned to family members or invested in their businesses, after an independent due diligence review is completed. Such distributions normally do not have any tax impact on the beneficiaries.

Beneficiaries

While the beneficiaries of the safety net are often broadened to include the spouse of a descendant, the incentives and the opportunity to participate in the family bank are generally restricted to blood family members. After the client decides on the incentives to incorporate in the trust, he or she must then decide on which beneficiaries are entitled to receive those incentives (for example, does an incentive which supplements a teacher’s income extend to spouses of descendants?) and safety nets (for example, does the educational safety net extend to spouses of descendants?). This distinction must be thoroughly addressed by the drafter of the FIT.

The Family Incentive Trust: the Right Tool?

The Family Incentive Trust is just one part of the estate planning arsenal. But its strength is its ability to deal with the two most pivotal issues in the planning process: minimizing the inter-generational confiscation of wealth and reducing the damage of inherited wealth to a family. It is also designed to provide something which all parents hope their inheritance will ensure, but which few parents believe can really happen – it encourages responsible behavior by future generations.

Many parents have just begun to understand their own mortality. While some want to rule from the grave, more want to leave a positive legacy which will have lasting impact on their families and society at large. The Family Incentive Trust provides such a legacy.

Does the Family Incentive Trust assure good descendants? Absolutely not, but it does help make sure the ones who would have been good are not turned to the dark side by their inherited wealth. FIT gives protections and opportunities to future generations which might have been lost if the inheritance were dissipated by a lavish lifestyle of predecessor generations. Further, it provides a productive legacy to future generations.

Does the Family Incentive Trust assure that there will be no family conflicts over the trust in the future? No, in fact, the FIT is structured with the understanding that conflict is probably inevitable as the wealth of the trust grows. As much as possible, FIT tries to create checks and balances to minimize the conflict. Greed is a basic human tendency. By placing constraints on inherited wealth, the FIT is designed to inhibit the conflict which often arises when wealth has no constraints.

Does the Family Incentive Trust solve every estate issue? Absolutely not – any more than the living trust is the solution to every estate need. It is merely one more arrow in the quiver of estate planning tools, but a powerful one that lets the client’s desires drive the plan. As with most estate planning, the FIT is a tradeoff of choices – made when trying to protect the family from the adverse impact of an unearned wealth.

Restrictions on Inherited Wealth: Ruling From the Grave?

One of the most frequent criticisms on restricted inheritances is that it is a blatant attempt of existing generations to rule from the grave, by mandating that their value systems govern the behavior of future generations. The critique is fundamentally philosophical and takes many expressed and implied forms, including the following:

The parents did a bad job, now they want to do from the grave what they could not do during life. There is some truth in this statement. Many of today’s millionaires survived the depression, went off to World War II, and came home determined to make a better life for their children. Now as they look back on their legacy, many wonder whether they just spoiled their children and are, therefore, concerned that the wealth they worked so hard to create will create an even greater negative legacy.

However, the truth of the issue only supports the need for something like the Family Incentive Trust. Having spoiled their children, do they just throw in the towel, with the expectation that the combination of their poor parenting skills and passage of wealth will only magnify the personality defects in their children? The goal of a FIT is not punitive, rather it is designed to place reasonable constraints which foster positive actions. It may not work with the first generation, but perhaps succeeding generations will be protected from their parent’s dissipation of the wealth and the adverse impact of silver spoon raising.

Parents are paying their heirs to do what they think is important. Paying an heir to do something they do not want to do is courting disaster. For example, paying a mother to stay at home with a child when she wants to work outside the home may hurt both the mother and child. Instead, the FIT is designed to provide incentives which provide enough money to encourage people to make positive decisions. For example, providing $5,000 annually to a college student with a B average is not enough to pay him to go to school, but it may sure provide encouragement. The key is that the payment is geared to a level which encourages, but does not pay for the desired activity. And yes, the values are the parent’s perspectives of what is important, but it is the parent’s money.

The Specter of a Boney Hand Reaching Out of the Grave Creates a Visual Image. It is without doubt a great visual image, but it is also a distorted one. The FIT should not be structured as a mechanism for a control freak to micro-manage the lives of his or her family from the grave. Rather, it is a means for a caring parent to provide opportunities and incentives to a family, without incurring the harmful aspects of wealth.

Moreover, restrictions on an inheritance is a fundamental part of any estate plan. For example, by their nature, Q-TIP trusts, minor’s trusts, and family partnerships have long been used to restrict a beneficiary’s access to his or her inheritance. The FIT carries on this basic perspective of estate planning.

In many cases, a beneficiary’s personality foibles and defects become magnified as an unintended result of receiving too much money too early. For example, over many years a grandfather and father placed money in a custodial account to fund a grandchild’s college education. By the age of 21 the child had dropped in and out of college a few times and went to his grandfather asking for the distribution of $210,000.00 held in his custodial account. When asked why, the child’s said that he wanted to discover himself and go to Europe for a year. The grandfather’s response was an emphatic no and an insistence that the child return to college. After receiving a demand letter from his grandson’s attorney, the grandfather was forced to distribute the funds to the grandchild who disappeared in Europe. Unfortunately, these funds which had been set aside with the expectation of funding a college education created an opposite result.

Wealth is a powerful tool, but as with anything powerful, its unrestricted power can be devastating. If a client knows something stands a good chance of harming his or her family, are he or she more or less responsible by placing limitations on the source of the harm? As stated by Swan Hunt [xxviii], the daughter of H.L. Hunt. For a person of wealth to think of handing it down to a child is almost like handing down a gun… Inherited wealth does more harm than good… it eats away at your self-esteem. More people resent you than admire you. You never know who is approaching you for what agenda.

If clients restricted access to their wealth (while providing a safety net), what is the worst that may happen to their families? They might have to make it on their own – not such a bad thing.

It is wrong to try and use the client‘s values to influence the behavior of future generations. Virtually everything done in the estate planning process influences behavior. It is naïve to think that an inheritance has a neutral impact. The central question which must be addressed (particularly when dealing with more remote heirs) is how sensibly (with knowledge and forethought) and positively to try to influence the character of future generations. Not dealing with the issue is perhaps the worst legacy a client can leave for his or her heirs.

This criticism basically carries with it the perspective that one person cannot and should not place their value systems on another. However, it ignores the fact that one of the primary parental responsibilities is to mold the character of the children. That responsibility does not cease just because someone reaches age 18 or 21. Many of the Incentive Trust Programs are flexible enough to provide benefits to children whose character is already well developed (children in their 30’s) by providing current income to children and incentive-based programs for grandchildren whose character is yet to be developed. Using a living document, flexibility can be placed in the plan to allow the values and characters to be changed.

Moreover, the structure of any incentive-based planning process should stress the positives, rather than the negatives. The more negative the provisions of a family trust, the greater the likelihood it will adversely impact future generations.

Just Trust the Children. Many critics say that placing restrictions on wealth creates a psychological issue of parents not trusting children and grandchildren. What the critics fail to recognize is that the impact of this perceived lack of trust may be less significant than the impact of an unfettered inheritance. Moreover, in most cases it is not a lack of trust, but a perception of the reality of the impact of wealth which drives the process. The children may resent not being able to spend Dad’s wealth, but the FIT may also require them to develop the ambition to make it themselves.

A It‘s the Kids Money. This implied criticism underlies many of the questions about restricted wealth transfers. It inherently states the children have some vested ownership in their parent’s assets. Ninety percent of today’s millionaires are self-made. Sixty-six percent are self-employed. There might be some validity to this argument if a parent inherited the wealth and was now trying to restrict the inheritance of his or her children. But even here, many individuals who have inherited wealth, more than others, recognize the devastating impact of wealth. It is not the kids’ money, and a parent has a responsibility to protect his or her family from any danger which he or she perceives may hurt that family. This is the legacy that a responsible parent should leave.

Flexibility

Some people have expressed concern about the inflexibility of any incentive-based trust, especially a dynasty trust. The concern seems to revolve around the following issues.

Because the trust is irrevocable, it is inflexible.

Because values change over time, the values the parent places in the trust today may not apply tomorrow. For example, changes in technology and society may make parts of the trust obsolete.

The discretionary nature of the trust opens trustees up to possible litigation.

The trustees may retain too much arbitrary authority.

However, the author believes that many of these issues can be minimized (but not eliminated) by flexible drafting which creates a Living Document. [xxix] Some of the flexible drafting approaches include the following:

Flexible Distributions